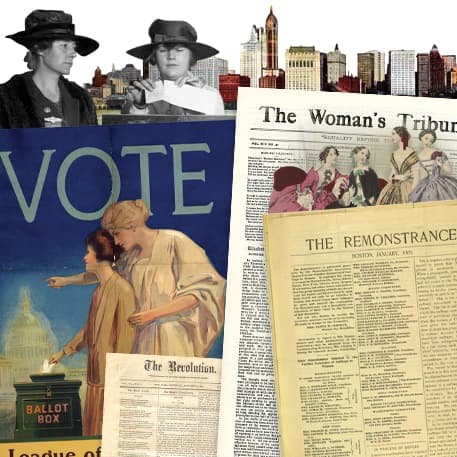

These are the writings of the most influential and outspoken women of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, preserving a record of the Women’s Rights and Woman Suffrage movements as told through their leaders’ voices.

The writings address other issues of the time as well—slavery, abolition, the Civil War, the Fifteenth Amendment, the rise of consumerism, the role of religion in family life, and the increase in immigration.

At a glance

1830–1913

8+ decades of major activists—Amelia Bloomer, Mary Church Terrell—and hundreds of other history changers.

9

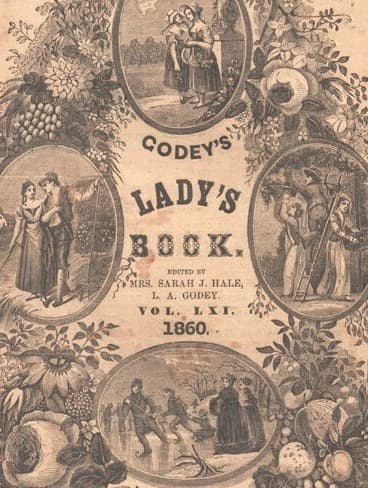

Nine titles. Every extant issue. Full runs of the most sought, including Godey's and The Woman's Tribune.

Publications include

Godey's Lady's Book

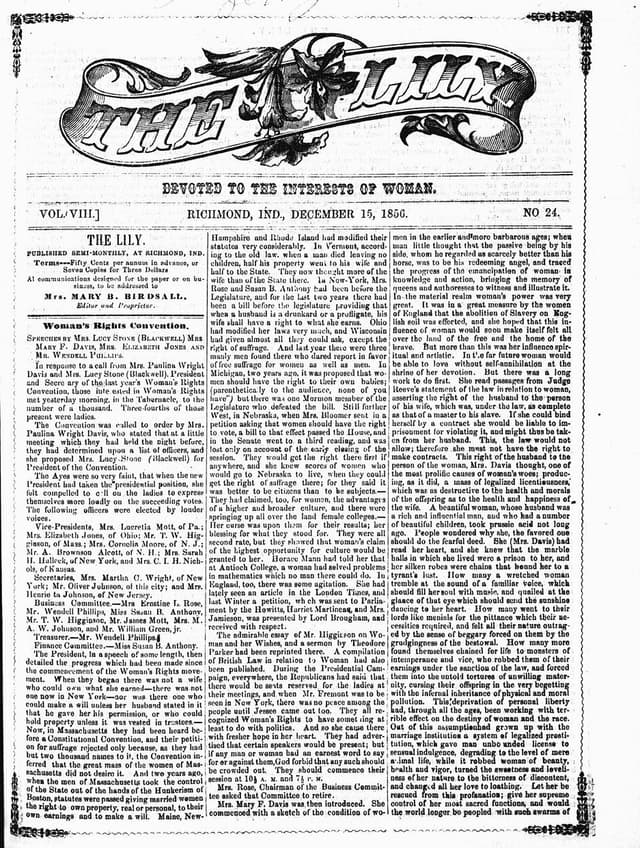

The Lily (1849-1856)

National Citizen and Ballot Box (1878-1881)

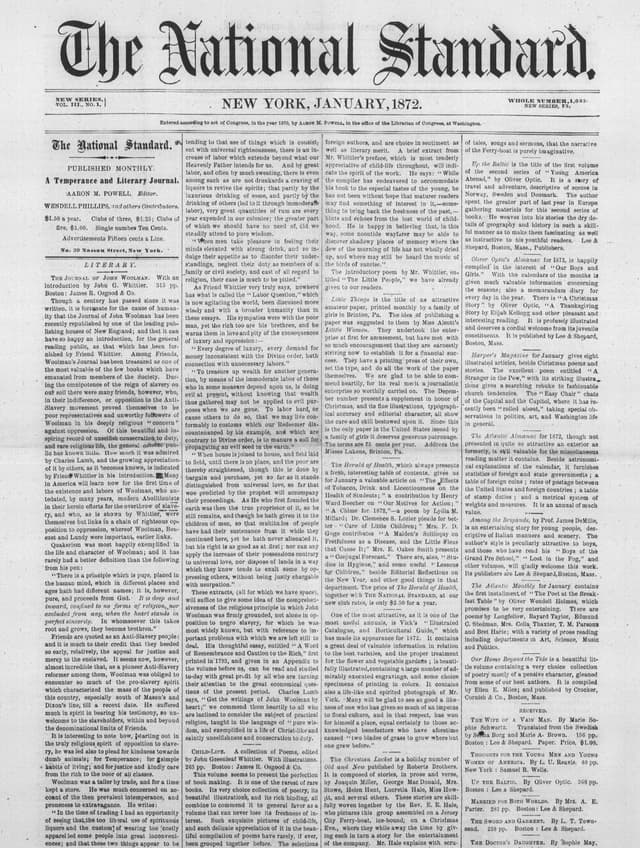

The National Standard: A Women’s Suffrage and Temperance Journal (1870-1872)

The New Citizen (1909-1912)

The Revolution (1868-1872)

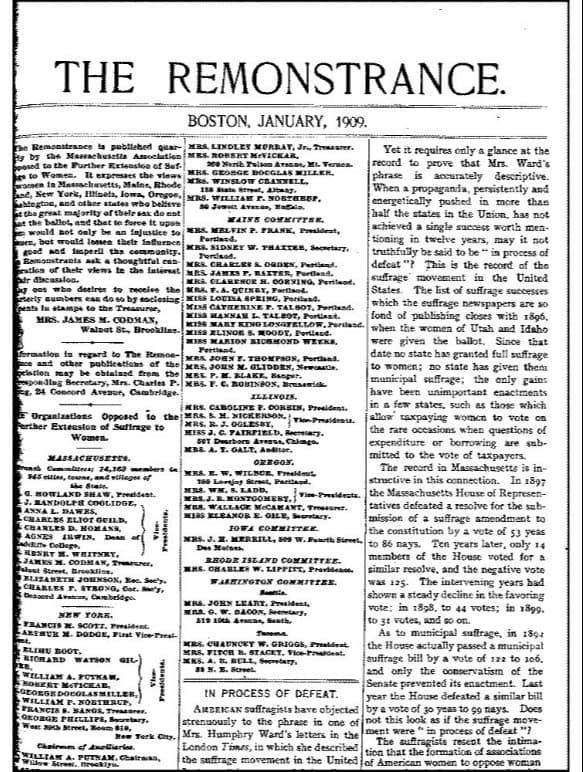

The Remonstrance (1890-1913)

The 19th Amendment Victory (1762-1923)

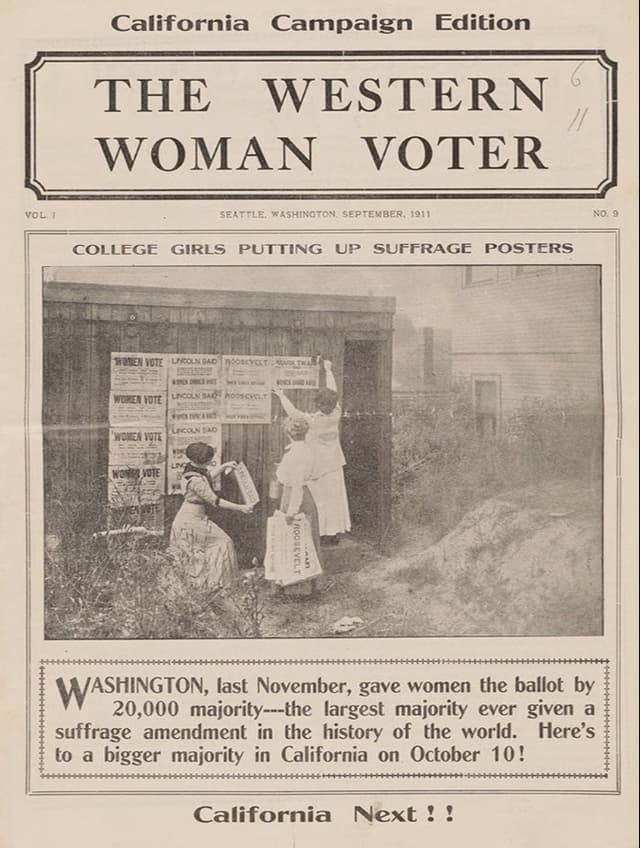

The Western Woman Voter (1911-1913)

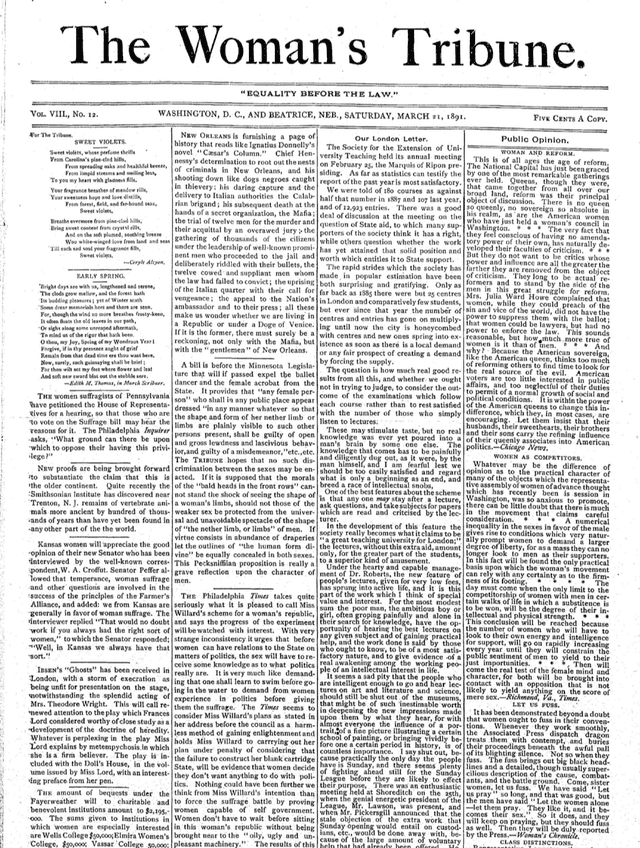

The Woman’s Tribune

Content highlights

Godey's Lady's Book (1830-1878)

Godey’s Lady's Book is considered among the most important resources for examining nineteenth-century American life and culture. Over time, it evolved into a key literary magazine featuring celebrated authors like Harriet Beecher Stowe and Edgar Allan Poe.

The Woman's Tribune (1883-1909)

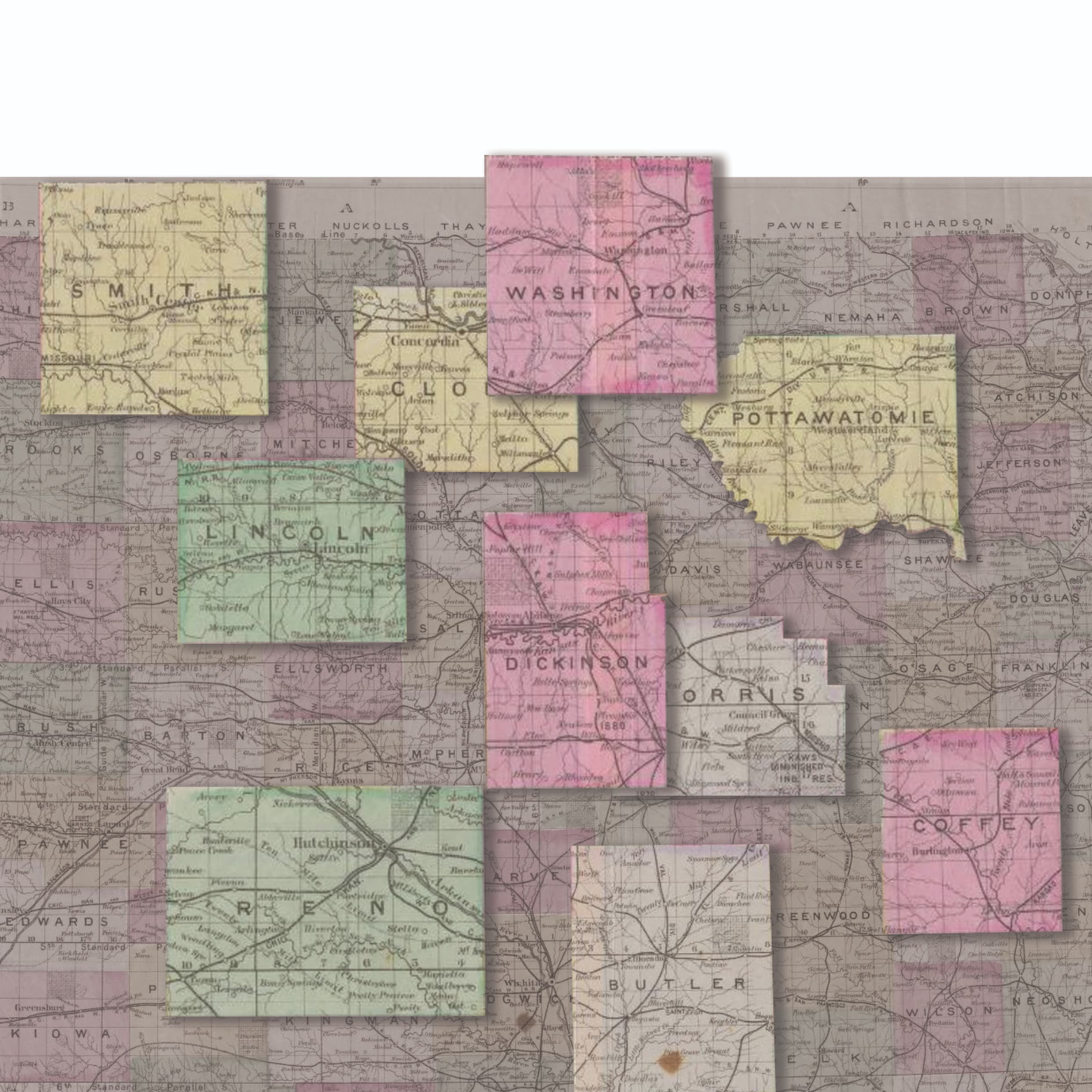

The Women’s Tribune was the second-longest-running woman suffrage newspaper and the first published by a woman. Clara Bewick Colby aimed to connect suffrage to other issues important to women, especially those in rural areas of the Midwest and West.

The National Standard (1870–1872)

In 1870, The National Standard launched as a monthly, supporting both the Woman Suffrage and Temperance movements. Within the year, it changed to a daily newspaper focusing on women’s political rights, suffrage, and social reforms.

The Lily (1849–1856)

The first newspaper for women, The Lily began as a temperance journal and became more radical with Elizabeth Cady Stanton writing as “Sunflower” and calling for changes in laws unfair to women and for dress reform.

The Western Woman Voter (1911–1913)

Following the passage of suffrage in Washington State, The Western Woman Voter served as a progressive forum for its publisher, Adella Parker. It kept women in each of the suffragist states informed of the civic activities of women voters elsewhere.

The Remonstrance (1890–1913)

The Remonstrance was the official publication of the Massachusetts Association Opposed to the Further Extension of Suffrage to Women. It was a forum for women who believed that the great majority of their sex did not want the ballot.

Want a trial?

Free, 30-day trial offered with training

Flexible pricing options, tailored to your institution's needs

Ask your sales rep about collection packages that offer the best value