African American Newspapers delivers a wealth of information about cultural life and history during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Its coverage is rich in firsthand accounts of events; analyses of issues; articles on business, world travel, and religion; descriptions of abolitionist campaigns, freedman aid, and other social-reform efforts; and biographies, statistics, essays, poetry, prose, and advertisements.

At a glance

14

historically important, full-run newspapers

99%

accuracy with manually rekeying

Black man reading newspaper by candlelight, 1863

Publications include

Freedom’s Journal , 1827-1829

The Liberator, 1831-1865

The National Era, 1831-1860

The Colored American, 1837-1841

National Anti-Slavery Standard, 1840-1870

The North Star, 1847-1851

Frederick Douglass’ Paper, 1851-1855

The Christian Recorder, 1854-1902

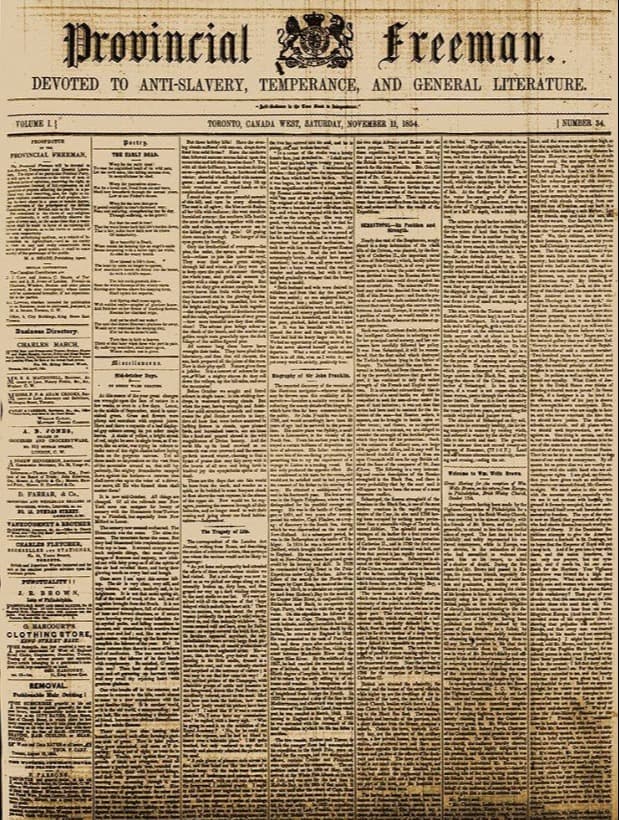

Provincial Freeman, 1854-1857

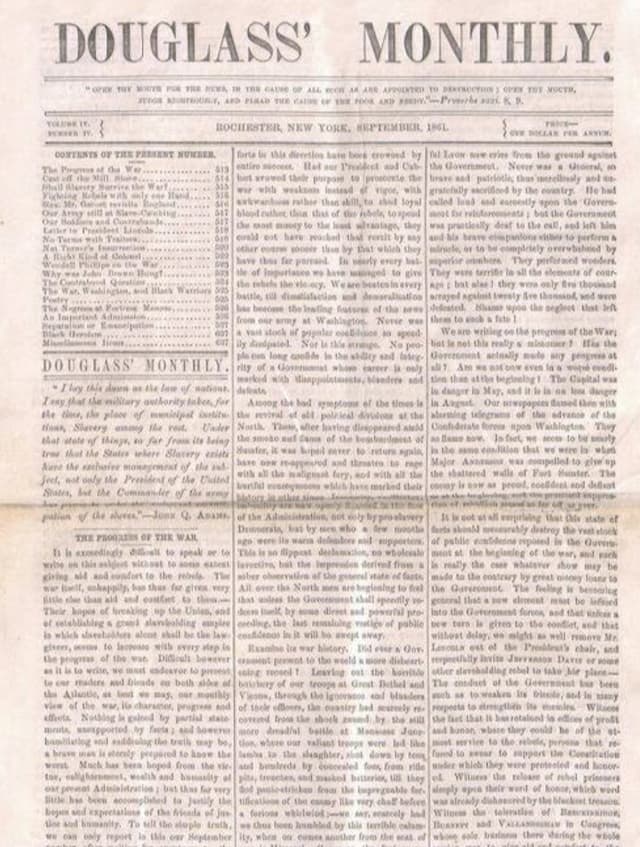

Douglass’ Monthly, 1858-1863

The Freedmen’s Record, 1865-1874

The Negro Business League Herald, 1909

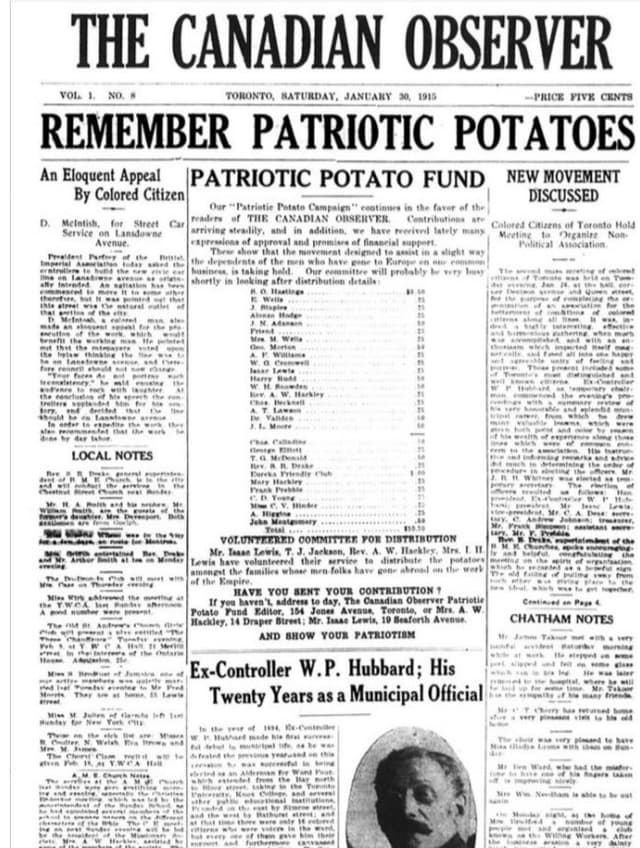

The Canadian Observer, 1914-19

The Weekly Advocate, 1837

The Charlestown Gazette rekeyed to 99% accuracy

Manually rekeyed for accuracy and accessibility

Optical Character Recognition (OCR) is a valuable tool for digitizing newspapers and other printed materials. However, older materials with nonstandard fonts can pose challenges for OCR technology.

Our North American collections are manually rekeyed to ensure 99% accuracy. This meticulous approach not only makes the content easy to read but also meets accessibility standards for the visually impaired. Also, we've structured the articles to enable richer text and data mining and to make citing easier.

Content higlights

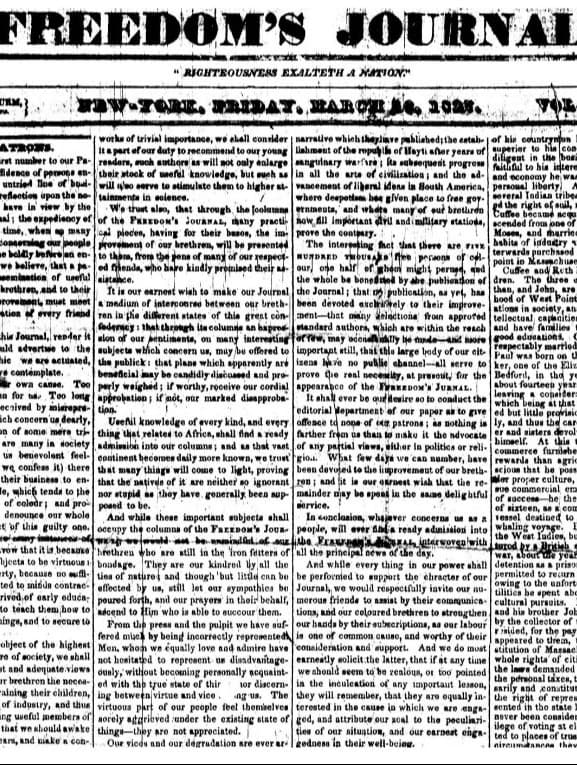

Freedom's Journal

Freedom’s Journal was the first American newspaper written by Blacks for Blacks. From the beginning, the editors felt “… that a paper devoted to the dissemination of useful knowledge among our brethren, and to their moral and religious improvement..."

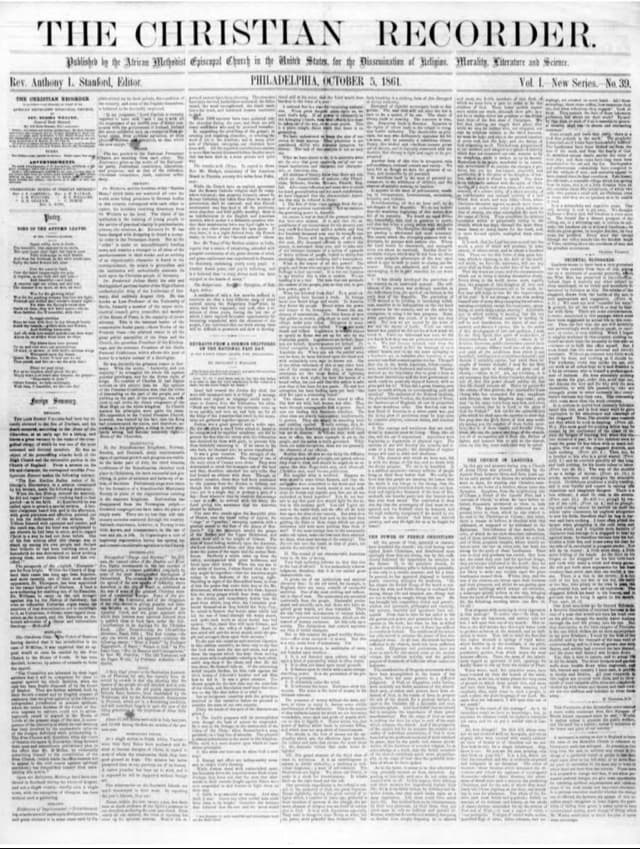

The Christian Recorder

Published by the African Methodist Episcopal Church in the United States for "the Dissemination of Religion, Morality, Literature and Science.” The newspaper covers the Civil War Black regiments and the ecclesiastical fight against Jim Crow.

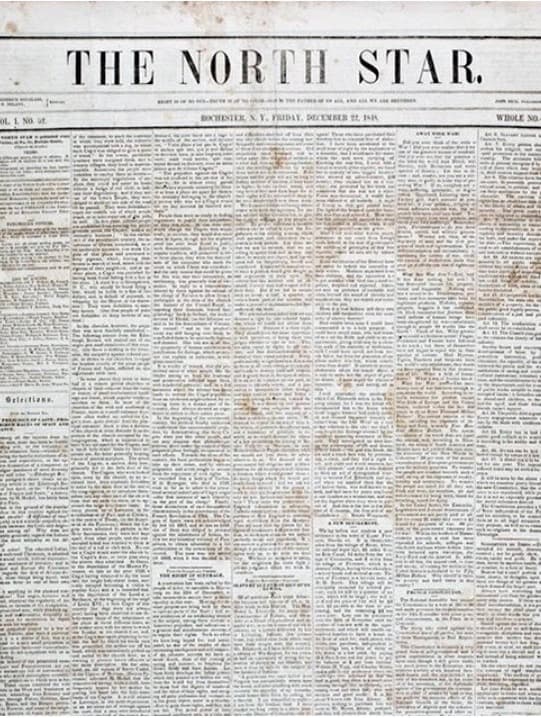

The North Star

Frederick Douglass created his first publication, The North Star, in 1847, after fleeing slavery and traveling to England, where friends furnished him with enough money to purchase his freedom and establish himself in the publishing business.

Provincial Freeman

The Provincial Freeman, published weekly by Canadian Blacks in Ontario (formerly Canada West), aimed to transform former slave refugees into model citizens. Mary Ann Carey became the first Black North American female editor and publisher.

Douglass’ Monthly

Frederick Douglass started his Douglass' Monthly in 1858 as a magazine format, different from the weekly newspaper style of his earlier publications. It focused on the abolitionist cause, but also tackled women's rights and social justice issues.

Canadian Observer

From 1914 to 1919, The Canadian Observer was considered “The Official Organ for the Coloured People in Canada.” The newspaper promoted racial politics and social activism, contributing to the rise of racial consciousness.

Want a trial?

Free, 30-day trial offered with training

Flexible pricing options, tailored to your institution's needs

Ask your sales rep about collection packages that offer the best value